The late John Ryan (1931-1979) was a passionate Australian Comic Historian or 'Panelologist', as he liked to be called. His seminal book 'Panel By Panel: an Illustrated History of Australian Comics' published in 1979 shortly before his death remains a major reference work on the Australian Comics medium. At some future date, Comicoz, with the full permission of the Copyright holder, plans to reprint and update this famous Australian book. This Tab on this Comicoz website (and the Tabs above labelled Part One: Newspaper Strips and Part Two: Comic Books) are both the beginnings of an attempt to work on this project. It was a great honour to accept, on behalf of John's family, the 2015 Platinum Ledger Award ("For Excellence in Australian Comics"); and wonderful to know the Australian comics community still acknowledges his pioneering works in this field of popular culture.

The idea behind these Tabs on my Comicoz website, is to allow the General Public and Comic Strip and Comic Book Historian an opportunity to read John Ryan's book (long out of print). I am especially interested in hearing from anyone who knows of any errors contained in the text. (Write to me via the "More..." then Contact Tag above or via my email address [email protected] ).

The site CAN be used as a reference tool, but I do ask that you cite it and acknowledge the Copyright within, which is owned by The Estate of John Ryan. A full citation should read something like this:

Ryan, John (1979). Panel By Panel: An Illustrated History of Australian Comics. Cassel: Sydney. http://www.comicoz.com/panel-by-panel.html [Accessed on line 19th November 2015]

On this page I plan to add any corrections supplied by anyone who can give me proof of any errors contained in the book or text contained within Part One and Part Two. The Tab labelled Part Three will be an attempt to record Australian comics history after the publishing of John's book. That is, the history of Australian Newspaper Strips and Comic Books since 1979. ANYONE who was involved in the scene is welcome to write to me (or write an article themselves!) and I shall include it in Part Three's section.

Of course, time constraints prevent me from writing and researching as much as I would like. I have a full-time job (I work in the Emergency Department of a busy Queensland public hospital, usually co-ordinating the Psychiatric Emergency Centre), I am married (to Carlene, who does not share my passion for comics' history or otherwise), and we have (six) children and grandchildren (ten, when I last counted). So, I have to spread myself around! I also - from time to time - seek to find the time to publish comic-related books (which you will, no doubt, have seen on this website) and I have even more interests outside of all of this! But this is my passion: the contributing and recording of the Australian History of this neglected, and sometimes reviled, form of popular culture that we call -- comics.

The idea behind these Tabs on my Comicoz website, is to allow the General Public and Comic Strip and Comic Book Historian an opportunity to read John Ryan's book (long out of print). I am especially interested in hearing from anyone who knows of any errors contained in the text. (Write to me via the "More..." then Contact Tag above or via my email address [email protected] ).

The site CAN be used as a reference tool, but I do ask that you cite it and acknowledge the Copyright within, which is owned by The Estate of John Ryan. A full citation should read something like this:

Ryan, John (1979). Panel By Panel: An Illustrated History of Australian Comics. Cassel: Sydney. http://www.comicoz.com/panel-by-panel.html [Accessed on line 19th November 2015]

On this page I plan to add any corrections supplied by anyone who can give me proof of any errors contained in the book or text contained within Part One and Part Two. The Tab labelled Part Three will be an attempt to record Australian comics history after the publishing of John's book. That is, the history of Australian Newspaper Strips and Comic Books since 1979. ANYONE who was involved in the scene is welcome to write to me (or write an article themselves!) and I shall include it in Part Three's section.

Of course, time constraints prevent me from writing and researching as much as I would like. I have a full-time job (I work in the Emergency Department of a busy Queensland public hospital, usually co-ordinating the Psychiatric Emergency Centre), I am married (to Carlene, who does not share my passion for comics' history or otherwise), and we have (six) children and grandchildren (ten, when I last counted). So, I have to spread myself around! I also - from time to time - seek to find the time to publish comic-related books (which you will, no doubt, have seen on this website) and I have even more interests outside of all of this! But this is my passion: the contributing and recording of the Australian History of this neglected, and sometimes reviled, form of popular culture that we call -- comics.

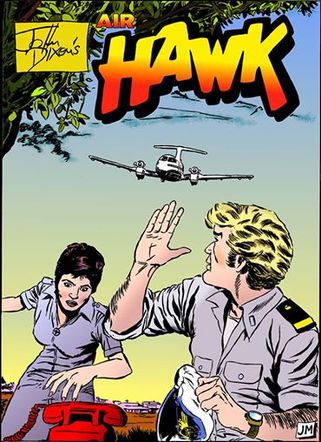

Air Hawk Copyright John Dixon, with Art and Colouring by Jeremy Macpherson.

Air Hawk Copyright John Dixon, with Art and Colouring by Jeremy Macpherson.

I would like to begin by acknowledging all the wonderful help of Jeremy Macpherson here on this, and Part One and Two of the PANEL by PANEL transcriptions. What could have taken me months to work out (despite tips by fellow comics publisher and historian Matt Emery!), has been completed for me (and at no cost) by the wonderful generosity of Jeremy. Thank you, Jeremy, from the bottom of my heart....

I am going to begin this page (after all these ramblings!) with the Introduction of John's book, as published in the Panel By Panel book. Following the Introduction, the corrections that have been discovered since the book was published in 1979 will be listed on this page, and once verified, added to the text. Somehow (I am not sure how, as I write this!) I will ensure that the corrected text will have a means of identifying the variation from the original published version within the text. (One possibility is a different colour being added to the text that has been modified.)

I shall leave the John Ryan-written article, "A Short History on Australian Comics" at the end of the page, for the casual reader who may seek to read a short, concise history of the medium (to about 1973, when the article was thought to be written)...

So, without further ado, here that follows is John Ryan's Introduction to his book, Panel by Panel: An Illustrated History of Australian Comics.

I am going to begin this page (after all these ramblings!) with the Introduction of John's book, as published in the Panel By Panel book. Following the Introduction, the corrections that have been discovered since the book was published in 1979 will be listed on this page, and once verified, added to the text. Somehow (I am not sure how, as I write this!) I will ensure that the corrected text will have a means of identifying the variation from the original published version within the text. (One possibility is a different colour being added to the text that has been modified.)

I shall leave the John Ryan-written article, "A Short History on Australian Comics" at the end of the page, for the casual reader who may seek to read a short, concise history of the medium (to about 1973, when the article was thought to be written)...

So, without further ado, here that follows is John Ryan's Introduction to his book, Panel by Panel: An Illustrated History of Australian Comics.

INTRODUCTION

Comics, it seems, have always been a part of my life. I think part of my fascination with the medium stems from the fact that I was one of the first generation to grow up with American comic books. Apart from giving me a necessary escape world that grown-ups seldom entered, comic books assisted my interest in reading and gave me a common interest with most of the other kids of Charles Street, Forest Lodge, where I spent most of my early life. Comic books, along with radio serials and going to the flicks on Saturday afternoon, were a very important part of our lives. Comics did not have to be thrust upon us. Regardless of their contents, they were considered welcome diversions from the more mundane reading matter that was thrust at children. If our teachers had understood our willing acceptance of this appealing form of communication and adapted it to our educational needs, I’m sure we would have learned a great deal more and much of our learning would have been far more enjoyable.

While I read or glanced at most of them, most newspaper strips did not have any great appeal for me until I entered my teens. Since the bulk of newspaper strips were aimed at an adult audience, my slow acceptance of them is understandable. Gradually, I began to appreciate many aspects of the newspaper strip. It became obvious that apart from fulfilling their main function of entertaining the reader, they were contemporary documents that reflected many historical and sociological aspects of our society. They recorded the fashions, fads, idioms, and prejudices of the period. A re-examination of comic books revealed that they, too, contained their share of such reflections.

For many years I have waited for the publication of books devoted to Australian comic strips. While there have been books on our humorous and editorial cartoons, there have been none that specifically examined our comic strips. Over the last decade both Europe and the USA have been well-served in this area, but nothing emerged on the local scene. It wasn’t until I was asked to prepare the Australian entries for The World Encyclopedia of Comics that I began to realize why there was an absence of such books — there were no basic reference works on the subject. When it comes to examining most fields we are usually reliant on previously published material. Even if (often with hindsight) we don’t agree with some of their assessments, we are indebted to previous writers for instant reference points or little-known facts which help take some of the drudgery out of the research.

Like most people, I would rather read a book than write one. But as I had been collecting examples and information about locally drawn comics since the early ’sixties it seemed that, if I wanted to read books on this subject, I should do the spade-work in providing some kind of basic reference. Expanding on the limited amount of information in my files was not an easy task. It involved many trips to the libraries in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide and poring through thousands of old newspapers and magazines; trying to track down many comic artists and publishers who were no longer connected with the field and then interviewing them; and writing hundreds of letters. It also meant enlisting the aid of many local collectors to conduct additional research or double-checking for me. The brief acknowledgement, elsewhere, hardly seems a fitting reward for that generous assistance.

To assist future researchers and students, I have placed considerable emphasis on names, titles, and dates through this book. Most of this information has not been published previously. While it has been necessary to touch upon the social and political context in some areas I have restricted my examination basically to the historical progression of comics in this country. Where possible, I have given biographical details of the artists concerned for it is important to know something of those who have contributed to the field. Obviously, it is easier to obtain information on more recent artists, and it is a matter of regret that very little has been recorded about our earlier comic strip artists, particularly those from the ’twenties and ’thirties. It would appear indicative of our comic artists’ standing with newspapers and magazines that so little has been written about them until quite recently.

Where possible, reproductions in this book have been made from original artwork in my collection. Sadly, in too many cases, no originals are known to have survived. We have no central body, such as the Museum of Cartoon Art in the USA, dedicated to the collection and preservation of our comic art heritage. But for the zeal of private collectors, examples of many of our major comic strips would be lost forever. While it is too late to retrieve most of the older work, some organized effort should be made to preserve examples of Australian comic strips from this point onwards. Otherwise, future historians in the field will be mourning a lack of examples of The Potts, Air Hawk, Basil, Snake Tales, The Warrumbunglers and so on, just as we currently bemoan missing examples of You & Me, Fat and His Friends, Us Fellers and others.

While it is possible to reach a consensus on the greatness of certain strips and artists, their numbers are small. Outside of this select group, the worthiness of a particular strip or artist becomes a matter of subjective judgment. While I have tried to be objective in my approach, students of the field are encouraged to make their own assessment of strips and styles and not be swayed by any of my subjectivity that has crept through. Comics are a medium of communication and, if a strip does not communicate to an individual, all the critical hyperbole in the world just becomes an academic exercise.

When examining the comics medium attention should be paid to what the strips are, in fact, saying. There is a story told about Reg Smythe and his Andy Capp strip. Not wanting to waste time drawing detailed backgrounds, Smythe often preferred to draw a brick wall. Some academics, in discussing the comic, have seen Andy as trapped by his working-class environment. Closer to home, I once assisted some media students who were making a term project film on Australian comic strips and cartoons. On reading the script my eyebrows, in the best comic strip tradition, jumped into the air. In a section dealing with Ginger Meggs, the script called for the narrator to say:

‘Ginger could be seen as a reflection of some characteristics of the labour movement. Bancks was himself the son of an Irish railway worker. Perhaps Ginger mockingly wears his waistcoat in the fashion of a union official. His monkey, then, can be seen as fulfilling the role of union members whose kid gloves could never cause any major social disruption. The workers are, in effect, being made monkeys of. Minnie wears hand muffs — is she frigid? Ginger’s Mum wears a tent

— is she pregnant? Ginger’s father wears Mo make-up — is he gay?’

Could this be the same Ginger Meggs I had been reading since I was a small boy? On querying the author of the script I was told, ‘You can read anything you like into comics and cartoons’. Perhaps you can — but I’d hasten to suggest that Snake Tales, for example, has more to do with the born losers of this world than it has to do with phallic symbols. Fortunately, the particular section devoted to Ginger Meggs was deleted when I informed the author that the monkey, Tony, did not wear gloves. The whole concept had been built on a false premise. There is nothing wrong with speculating on the messages that might be contained in a comic provided those who are speculating do not lose sight of what the comics actually reflect and are saying.

For the general reader, I hope this book will prove a source of enlightenment, nostalgia, and a means to identifying many long-forgotten strips and artists. For those with more academic interests, I hope it will prove a useful research tool in presenting further examinations of the field.

John Ryan Upper Mt Gravatt, Qld 1979

Comics, it seems, have always been a part of my life. I think part of my fascination with the medium stems from the fact that I was one of the first generation to grow up with American comic books. Apart from giving me a necessary escape world that grown-ups seldom entered, comic books assisted my interest in reading and gave me a common interest with most of the other kids of Charles Street, Forest Lodge, where I spent most of my early life. Comic books, along with radio serials and going to the flicks on Saturday afternoon, were a very important part of our lives. Comics did not have to be thrust upon us. Regardless of their contents, they were considered welcome diversions from the more mundane reading matter that was thrust at children. If our teachers had understood our willing acceptance of this appealing form of communication and adapted it to our educational needs, I’m sure we would have learned a great deal more and much of our learning would have been far more enjoyable.

While I read or glanced at most of them, most newspaper strips did not have any great appeal for me until I entered my teens. Since the bulk of newspaper strips were aimed at an adult audience, my slow acceptance of them is understandable. Gradually, I began to appreciate many aspects of the newspaper strip. It became obvious that apart from fulfilling their main function of entertaining the reader, they were contemporary documents that reflected many historical and sociological aspects of our society. They recorded the fashions, fads, idioms, and prejudices of the period. A re-examination of comic books revealed that they, too, contained their share of such reflections.

For many years I have waited for the publication of books devoted to Australian comic strips. While there have been books on our humorous and editorial cartoons, there have been none that specifically examined our comic strips. Over the last decade both Europe and the USA have been well-served in this area, but nothing emerged on the local scene. It wasn’t until I was asked to prepare the Australian entries for The World Encyclopedia of Comics that I began to realize why there was an absence of such books — there were no basic reference works on the subject. When it comes to examining most fields we are usually reliant on previously published material. Even if (often with hindsight) we don’t agree with some of their assessments, we are indebted to previous writers for instant reference points or little-known facts which help take some of the drudgery out of the research.

Like most people, I would rather read a book than write one. But as I had been collecting examples and information about locally drawn comics since the early ’sixties it seemed that, if I wanted to read books on this subject, I should do the spade-work in providing some kind of basic reference. Expanding on the limited amount of information in my files was not an easy task. It involved many trips to the libraries in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide and poring through thousands of old newspapers and magazines; trying to track down many comic artists and publishers who were no longer connected with the field and then interviewing them; and writing hundreds of letters. It also meant enlisting the aid of many local collectors to conduct additional research or double-checking for me. The brief acknowledgement, elsewhere, hardly seems a fitting reward for that generous assistance.

To assist future researchers and students, I have placed considerable emphasis on names, titles, and dates through this book. Most of this information has not been published previously. While it has been necessary to touch upon the social and political context in some areas I have restricted my examination basically to the historical progression of comics in this country. Where possible, I have given biographical details of the artists concerned for it is important to know something of those who have contributed to the field. Obviously, it is easier to obtain information on more recent artists, and it is a matter of regret that very little has been recorded about our earlier comic strip artists, particularly those from the ’twenties and ’thirties. It would appear indicative of our comic artists’ standing with newspapers and magazines that so little has been written about them until quite recently.

Where possible, reproductions in this book have been made from original artwork in my collection. Sadly, in too many cases, no originals are known to have survived. We have no central body, such as the Museum of Cartoon Art in the USA, dedicated to the collection and preservation of our comic art heritage. But for the zeal of private collectors, examples of many of our major comic strips would be lost forever. While it is too late to retrieve most of the older work, some organized effort should be made to preserve examples of Australian comic strips from this point onwards. Otherwise, future historians in the field will be mourning a lack of examples of The Potts, Air Hawk, Basil, Snake Tales, The Warrumbunglers and so on, just as we currently bemoan missing examples of You & Me, Fat and His Friends, Us Fellers and others.

While it is possible to reach a consensus on the greatness of certain strips and artists, their numbers are small. Outside of this select group, the worthiness of a particular strip or artist becomes a matter of subjective judgment. While I have tried to be objective in my approach, students of the field are encouraged to make their own assessment of strips and styles and not be swayed by any of my subjectivity that has crept through. Comics are a medium of communication and, if a strip does not communicate to an individual, all the critical hyperbole in the world just becomes an academic exercise.

When examining the comics medium attention should be paid to what the strips are, in fact, saying. There is a story told about Reg Smythe and his Andy Capp strip. Not wanting to waste time drawing detailed backgrounds, Smythe often preferred to draw a brick wall. Some academics, in discussing the comic, have seen Andy as trapped by his working-class environment. Closer to home, I once assisted some media students who were making a term project film on Australian comic strips and cartoons. On reading the script my eyebrows, in the best comic strip tradition, jumped into the air. In a section dealing with Ginger Meggs, the script called for the narrator to say:

‘Ginger could be seen as a reflection of some characteristics of the labour movement. Bancks was himself the son of an Irish railway worker. Perhaps Ginger mockingly wears his waistcoat in the fashion of a union official. His monkey, then, can be seen as fulfilling the role of union members whose kid gloves could never cause any major social disruption. The workers are, in effect, being made monkeys of. Minnie wears hand muffs — is she frigid? Ginger’s Mum wears a tent

— is she pregnant? Ginger’s father wears Mo make-up — is he gay?’

Could this be the same Ginger Meggs I had been reading since I was a small boy? On querying the author of the script I was told, ‘You can read anything you like into comics and cartoons’. Perhaps you can — but I’d hasten to suggest that Snake Tales, for example, has more to do with the born losers of this world than it has to do with phallic symbols. Fortunately, the particular section devoted to Ginger Meggs was deleted when I informed the author that the monkey, Tony, did not wear gloves. The whole concept had been built on a false premise. There is nothing wrong with speculating on the messages that might be contained in a comic provided those who are speculating do not lose sight of what the comics actually reflect and are saying.

For the general reader, I hope this book will prove a source of enlightenment, nostalgia, and a means to identifying many long-forgotten strips and artists. For those with more academic interests, I hope it will prove a useful research tool in presenting further examinations of the field.

John Ryan Upper Mt Gravatt, Qld 1979

"A Short History on Australian Comics"

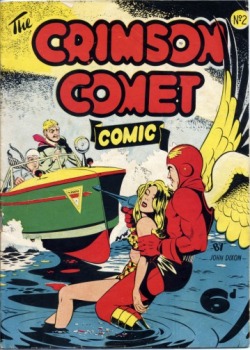

John Dixon's work from the Golden Age of Australian Comics

By JOHN RYAN

Almost since their inception, U.S. Comic books (“Yankee” or “American” comics as we called them) were available in Australia. My research leads me to believe that virtually every pre-Second World War U.S. comic book title (with the possible exception of the Fawcett line) was available in Australia. Like most of the kids in my street, I grabbed my copies of Amazing Mystery Funnies, Adventure, Pep, Wonderworld, Marvel Mystery, Silver Streak, etc just as avidly as my American counterpart. Consequently, it is not as strange as it may first appear to find Australians of my age group[1] with a fairly intimate knowledge of U.S. Golden Age comics.

English comic papers, it seemed, had always been with us – but most of my generation preferred the more colourful, action-packed American books to such English titles as Comic Cuts, Chips, Tip Top, Film Fun, Jingles, and others of the ilk. It is not surprising, then, that when supplies of U.S. comics ceased shortly after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, we felt cheated. The war didn’t worry us greatly – that was something that involved the ‘grown-ups. All we knew was that we could no longer get our Yankee Comics – and on this score, the sooner the war was over the better!

Up until 1941, the Australian comic industry was very small; with almost the entire output being devoted to reprints of U.S. newspaper strips. The main strips being reprinted were The Phantom, Buck Rogers, Skyroads (re-titled Hurrican Hawk) and Felix the Cat – with the latter being replaced in 1942 with Red Ryder! Because of newsprint restrictions, the publishing companies operated under a licence that would not allow them to operate under any continuing titles. Titles (such as Buck Rogers) that had been established prior to the War were allowed to continue with their numbering sequence…but new comics had to have a different title each issue (under the pretence that they were one-shot publications). Because of the lack of continuing titles and the complete absence of any publication date, it is very difficult to accurately date the many comics of this period.

With the curtailment of supplies from the U.S. (and reduced supplies from England) the local industry increased their output to capitalise on the market that had been virtually handed to them on a platter. Initially they increased the quantity of newspaper strip reprints and we saw such strips as Sgt. Stony Craig, Don Winslow, Alley Oop, Wash Tubs & Captian Easy, Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. But even these strips were hard to get during wartime restrictions – and those supplies that were obtained were soon used-up. After all, many comics were published on a weekly schedule. This situation, then, was responsible for the creation of the original Australian comic book, both drawn and written by local talent.

While many publishers tried their hand at this field, the most important publishers during the war years were N.S.W. Bookstalls, Offset Printing Co., K.G. Murray, Frank Johnson Publications, H.E. Hoffman and Syd Miller. In the immediate post-war years, they were joined by H. John Edwards and Syd Nicolls. With the lifting of newsprint restrictions in 1946, most publishers adopted a continuing title for various comics and, in some cases, even dated them.

A large percentage of the material from that [War] period was incredibly bad. It was crude in design, amateurish in execution and totally lacking in any understanding of the field of graphic art. If you consider this poor work, printed in black and white (sometimes on grey, blue or brown paper!) and enclosed in a three-colour cover, you can, perhaps, understand why my contemporaries and I yearned for the return of American comics. It might also help you to understand why Aussie comic addicts paid up to 40c for an American comic that had somehow made its way into the country. And this was in the days when a comic cost 5c and the average boy was lucky to get 10c per week pocket money.

While most of this early original material plumbed the depths of mediocrity, there was a small group of artists whose work was of a high standard. Artists such as Syd Miller (Molo, Red Gregory), Syd Nicholls (The Phantom Pirate, Middy Malone) and Hal English (Red Steele) were mature men, established in commercial art and cartooning field prior to the arrival of the local comic industry. Anything they produced was worth reading. The Syd Nicholls/Allied Authors and Artists group were responsible for the most titles devoted solely to Australian material (Fatty Finn, Middy Malone, Cooee, Tex Morton, and Rupert Rabbit Comics).

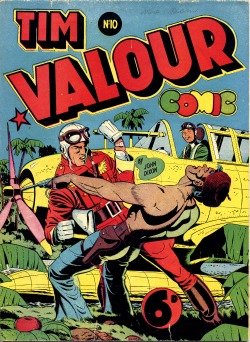

But it was the post-war years that brought into flower some of our finest comic-book artists. Stanley Pitt (Silver Starr, Yarmak). John Dixon (Tim Valour, The Crimson Comet, Catman), Monty Wedd (Captain Justice, The Scorpion), Phil Belbin (The Raven, Ace Bradley), Hart Amos and Vernon Hayles (both of whom produced mainly one-shots) – these were some of the men who made 1946 to the mid-1950s the Golden Age of Australian comic books.

During this period, with a few exceptions, I did not appreciate the local industry’s effort. All I could think about once the war had ended was that American comics would be back on sale very soon. But that was not to be! The Government of the day had imposed Import Restrictions on any item that was to be paid for in U.S. currency – and these restrictions remained in force until late in 1958. American comics re-appeared on the newsstands in 1959, after an absence of almost 18 years.

The immediate post-war years brought two interesting developments – both closely linked. K.G. Murray Publications decided to print their comics in colour and introduced three titles. The first was Climax – which showcased the talents of Amos, Hayles, Belbin, Bertram, Cocks and Lawson. All Australians – and seen in colour for the first time. Their second title was Superman and reprinted the adventures of the Man of Steel for the first time in this country. The third title was Captain Triumph which reprinted the adventures of that worthy being, along with Hack O’Hara, Pen Miller and other characters from the old Quality line.

From Melbourne, Atlas Publications struck back with their own contender in the Colour stakes, Captain Atom. Scripted by John Welles and drawn by Arthur Mather, this character was a blatant combination of Captain Marvel and Captain Triumph – twin brothers who made the transformation by mouthing the magic work “Exnor!” This comic also featured stories by Stan Pitt and Michael Trueman.

Because of Australia’s small population, it was not possible to reach out and sustain the type of circulation required to support the additional cost of colour reproduction, And so, in just under two years, the colour experiment was dropped on all the adventure titles. Only one publisher continued with colour: W.G. Publications. This company reprinted the Walt Disney line of characters and went from strength to strength, continuing to print in colour with good circulations [until the early 1980s].

The colour was gone from the adventure comic field – but the reprints of U.S. comic book characters stayed! It was the thin edge of the wedge which eventually killed the original Australian Comic. K.G. Murray added Superboy, Batman, Zatara, Aquaman, The Vigilante and other DC characters to their range of reprints… Larry S. Cleland reprinted the entire Fawcett line… Ayres & James reprinted many Quality characters, as well as continuing with their newspaper reprints… Atlas Publications handled the Prize/Headline group of characters (including Fighting American)… H. John Edwards reprinted both the Fiction House and MLJ line of characters and so on; until there were very few U.S. titles not being reprinted in Australia.

By the late 1950s, the reprints had taken over the field, leaving only a handful of Australian craftsmen remaining in the industry. In 1963, to all intents and purposes, original Australian comics were buried. The U.S. reprints who were responsible for the death were not at the graveside; they were too busy fighting off another assailant – the U.S. comic book. The reprint publishers were doomed from the beginning. Their thin, black and white efforts could not compete with the slick-looking, brightly coloured U.S. counterpart which sat next to them on the newsstands…and cost the same 12c price! It was not unusual to find a reprint released of a story that had appeared in a U.S. comic that had been on sale some months before. With that type of thinking (or non-thinking) that would allow this sort of thing to occur, it was not surprising that the Australian comic industry died.

[1] John Ryan was born in 1931

Almost since their inception, U.S. Comic books (“Yankee” or “American” comics as we called them) were available in Australia. My research leads me to believe that virtually every pre-Second World War U.S. comic book title (with the possible exception of the Fawcett line) was available in Australia. Like most of the kids in my street, I grabbed my copies of Amazing Mystery Funnies, Adventure, Pep, Wonderworld, Marvel Mystery, Silver Streak, etc just as avidly as my American counterpart. Consequently, it is not as strange as it may first appear to find Australians of my age group[1] with a fairly intimate knowledge of U.S. Golden Age comics.

English comic papers, it seemed, had always been with us – but most of my generation preferred the more colourful, action-packed American books to such English titles as Comic Cuts, Chips, Tip Top, Film Fun, Jingles, and others of the ilk. It is not surprising, then, that when supplies of U.S. comics ceased shortly after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, we felt cheated. The war didn’t worry us greatly – that was something that involved the ‘grown-ups. All we knew was that we could no longer get our Yankee Comics – and on this score, the sooner the war was over the better!

Up until 1941, the Australian comic industry was very small; with almost the entire output being devoted to reprints of U.S. newspaper strips. The main strips being reprinted were The Phantom, Buck Rogers, Skyroads (re-titled Hurrican Hawk) and Felix the Cat – with the latter being replaced in 1942 with Red Ryder! Because of newsprint restrictions, the publishing companies operated under a licence that would not allow them to operate under any continuing titles. Titles (such as Buck Rogers) that had been established prior to the War were allowed to continue with their numbering sequence…but new comics had to have a different title each issue (under the pretence that they were one-shot publications). Because of the lack of continuing titles and the complete absence of any publication date, it is very difficult to accurately date the many comics of this period.

With the curtailment of supplies from the U.S. (and reduced supplies from England) the local industry increased their output to capitalise on the market that had been virtually handed to them on a platter. Initially they increased the quantity of newspaper strip reprints and we saw such strips as Sgt. Stony Craig, Don Winslow, Alley Oop, Wash Tubs & Captian Easy, Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. But even these strips were hard to get during wartime restrictions – and those supplies that were obtained were soon used-up. After all, many comics were published on a weekly schedule. This situation, then, was responsible for the creation of the original Australian comic book, both drawn and written by local talent.

While many publishers tried their hand at this field, the most important publishers during the war years were N.S.W. Bookstalls, Offset Printing Co., K.G. Murray, Frank Johnson Publications, H.E. Hoffman and Syd Miller. In the immediate post-war years, they were joined by H. John Edwards and Syd Nicolls. With the lifting of newsprint restrictions in 1946, most publishers adopted a continuing title for various comics and, in some cases, even dated them.

A large percentage of the material from that [War] period was incredibly bad. It was crude in design, amateurish in execution and totally lacking in any understanding of the field of graphic art. If you consider this poor work, printed in black and white (sometimes on grey, blue or brown paper!) and enclosed in a three-colour cover, you can, perhaps, understand why my contemporaries and I yearned for the return of American comics. It might also help you to understand why Aussie comic addicts paid up to 40c for an American comic that had somehow made its way into the country. And this was in the days when a comic cost 5c and the average boy was lucky to get 10c per week pocket money.

While most of this early original material plumbed the depths of mediocrity, there was a small group of artists whose work was of a high standard. Artists such as Syd Miller (Molo, Red Gregory), Syd Nicholls (The Phantom Pirate, Middy Malone) and Hal English (Red Steele) were mature men, established in commercial art and cartooning field prior to the arrival of the local comic industry. Anything they produced was worth reading. The Syd Nicholls/Allied Authors and Artists group were responsible for the most titles devoted solely to Australian material (Fatty Finn, Middy Malone, Cooee, Tex Morton, and Rupert Rabbit Comics).

But it was the post-war years that brought into flower some of our finest comic-book artists. Stanley Pitt (Silver Starr, Yarmak). John Dixon (Tim Valour, The Crimson Comet, Catman), Monty Wedd (Captain Justice, The Scorpion), Phil Belbin (The Raven, Ace Bradley), Hart Amos and Vernon Hayles (both of whom produced mainly one-shots) – these were some of the men who made 1946 to the mid-1950s the Golden Age of Australian comic books.

During this period, with a few exceptions, I did not appreciate the local industry’s effort. All I could think about once the war had ended was that American comics would be back on sale very soon. But that was not to be! The Government of the day had imposed Import Restrictions on any item that was to be paid for in U.S. currency – and these restrictions remained in force until late in 1958. American comics re-appeared on the newsstands in 1959, after an absence of almost 18 years.

The immediate post-war years brought two interesting developments – both closely linked. K.G. Murray Publications decided to print their comics in colour and introduced three titles. The first was Climax – which showcased the talents of Amos, Hayles, Belbin, Bertram, Cocks and Lawson. All Australians – and seen in colour for the first time. Their second title was Superman and reprinted the adventures of the Man of Steel for the first time in this country. The third title was Captain Triumph which reprinted the adventures of that worthy being, along with Hack O’Hara, Pen Miller and other characters from the old Quality line.

From Melbourne, Atlas Publications struck back with their own contender in the Colour stakes, Captain Atom. Scripted by John Welles and drawn by Arthur Mather, this character was a blatant combination of Captain Marvel and Captain Triumph – twin brothers who made the transformation by mouthing the magic work “Exnor!” This comic also featured stories by Stan Pitt and Michael Trueman.

Because of Australia’s small population, it was not possible to reach out and sustain the type of circulation required to support the additional cost of colour reproduction, And so, in just under two years, the colour experiment was dropped on all the adventure titles. Only one publisher continued with colour: W.G. Publications. This company reprinted the Walt Disney line of characters and went from strength to strength, continuing to print in colour with good circulations [until the early 1980s].

The colour was gone from the adventure comic field – but the reprints of U.S. comic book characters stayed! It was the thin edge of the wedge which eventually killed the original Australian Comic. K.G. Murray added Superboy, Batman, Zatara, Aquaman, The Vigilante and other DC characters to their range of reprints… Larry S. Cleland reprinted the entire Fawcett line… Ayres & James reprinted many Quality characters, as well as continuing with their newspaper reprints… Atlas Publications handled the Prize/Headline group of characters (including Fighting American)… H. John Edwards reprinted both the Fiction House and MLJ line of characters and so on; until there were very few U.S. titles not being reprinted in Australia.

By the late 1950s, the reprints had taken over the field, leaving only a handful of Australian craftsmen remaining in the industry. In 1963, to all intents and purposes, original Australian comics were buried. The U.S. reprints who were responsible for the death were not at the graveside; they were too busy fighting off another assailant – the U.S. comic book. The reprint publishers were doomed from the beginning. Their thin, black and white efforts could not compete with the slick-looking, brightly coloured U.S. counterpart which sat next to them on the newsstands…and cost the same 12c price! It was not unusual to find a reprint released of a story that had appeared in a U.S. comic that had been on sale some months before. With that type of thinking (or non-thinking) that would allow this sort of thing to occur, it was not surprising that the Australian comic industry died.

[1] John Ryan was born in 1931

John Ryan

More of John Dixon's work from Australia's Golden Age

Information for this article was obtained from a booklet entitled 'John Ryan'. (Published by the late John Ryan as preparation for “a projected Fandom Profile” for Howard Siegal’s 'Comic Collectors Comments' column; giving no publication date – however, with details included, it seems likely to have been published in late 1973).

Further information was gathered from a John Ryan-published Fan-zine 'Boomerang' (Number #29: September 1973).

Article Edited by Nat Karmichael, August 31st 2009. Copyright The Estate of John Ryan 1979,

Reprinted and Edited with permission of the Copyright Owner.